Ex Votos: Stories of Miracles

by Mariolina Rizzi Salvatori

Ex-votos: I remember when and where I first saw them: 1947, the Sanctuary of Madonna Incoronata. My brother, a lieutenant in the Italian army, alive at the end of WWII, had since disappeared; my Mother had come on pilgrimage to the Sanctuary to pray for his safe return.

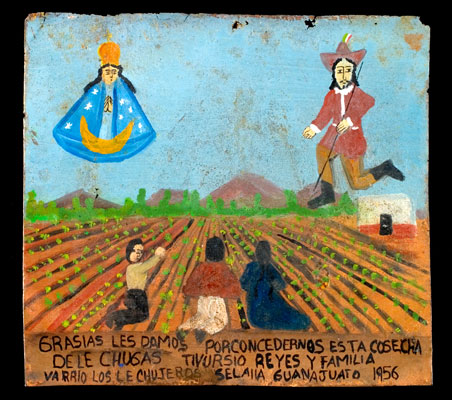

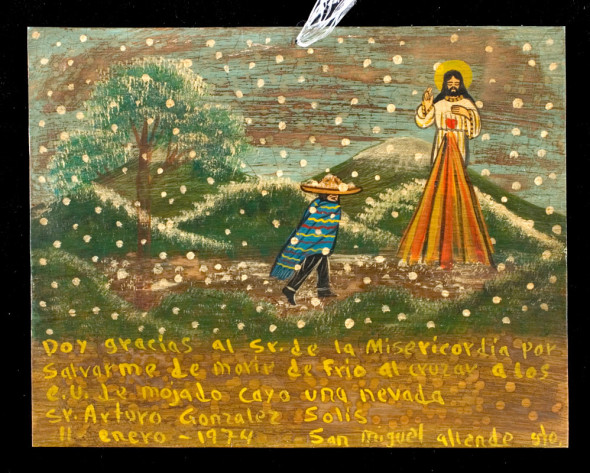

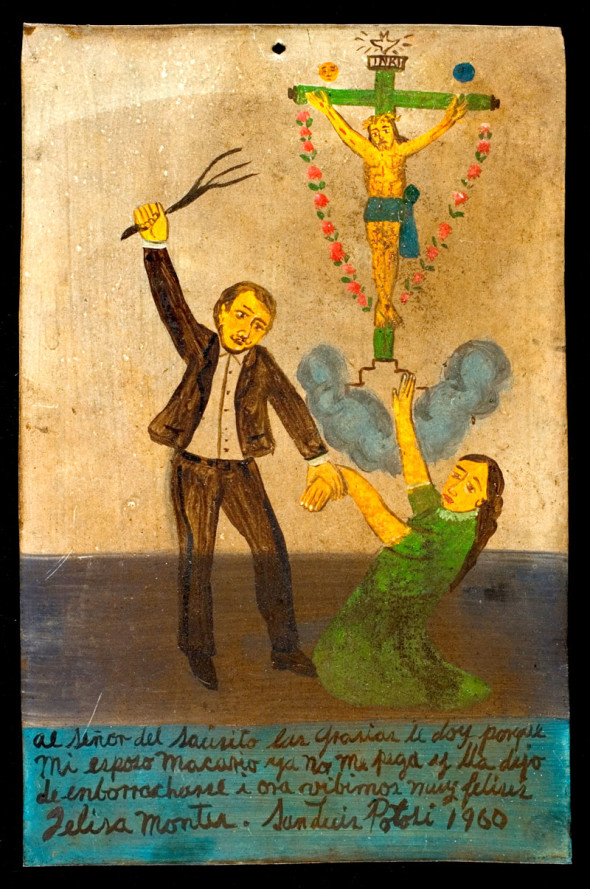

She had been absorbed in prayer for a long time, too long for a restless eight years old. I slid out of the pew and tiptoed to the main altar to take a closer look at the statue of Madonna Incoronata; then, following a group of pilgrims, I ventured behind it, where I found myself in front of hundreds of little colorful paintings nailed to the walls. What I saw mesmerized and frightened me: children falling off trees, balconies, cliffs; children fallen into wells, or plastered on the ground under a pile of bricks, a fallen horse, a cart, a truck; people on rudimentary operating tables with doctors, holding huge knives mid-air, tending to them–blood spouting out of wounds, mouths, ears; cows and horses giving birth; flames leaping out of buildings; bodies engulfed in flames. What I was looking at were ex votos, recently and most aptly defined as “the shortest of stories . . . [stories] which begin in worry and end in wonder . . . each a glimpse into a life of faith” (Nancy Haught). More pilgrimages followed to more sanctuaries. More ex votos for me to see and be haunted by. More opportunities for me to imagine what my Mother’s ex voto would look like, the story it would tell. But she never got to offer one: her worry never became wonder.

She had been absorbed in prayer for a long time, too long for a restless eight years old. I slid out of the pew and tiptoed to the main altar to take a closer look at the statue of Madonna Incoronata; then, following a group of pilgrims, I ventured behind it, where I found myself in front of hundreds of little colorful paintings nailed to the walls. What I saw mesmerized and frightened me: children falling off trees, balconies, cliffs; children fallen into wells, or plastered on the ground under a pile of bricks, a fallen horse, a cart, a truck; people on rudimentary operating tables with doctors, holding huge knives mid-air, tending to them–blood spouting out of wounds, mouths, ears; cows and horses giving birth; flames leaping out of buildings; bodies engulfed in flames. What I was looking at were ex votos, recently and most aptly defined as “the shortest of stories . . . [stories] which begin in worry and end in wonder . . . each a glimpse into a life of faith” (Nancy Haught). More pilgrimages followed to more sanctuaries. More ex votos for me to see and be haunted by. More opportunities for me to imagine what my Mother’s ex voto would look like, the story it would tell. But she never got to offer one: her worry never became wonder.

When in the late 1960s, my husband and I emigrated to this country, ex-votos and my fascination with them, became a part of the past we had left behind. Then, in the mid-1980s, unexpectedly, that past reconnected with me. While browsing in a shop in Philadelphia that specializes in Mexican, Caribbean, and South American artifacts, I spotted what I thought was an Italian ex voto. As I read the words under the image, I realized it was Mexican. I was startled. I did not know the tradition had traveled so far. The object ignited dormant memories—familial, religious—which, at this point in my life, I felt the need to make room for. I began to collect Mexican ex-votos, until recently the only ones I could find.

When in the late 1960s, my husband and I emigrated to this country, ex-votos and my fascination with them, became a part of the past we had left behind. Then, in the mid-1980s, unexpectedly, that past reconnected with me. While browsing in a shop in Philadelphia that specializes in Mexican, Caribbean, and South American artifacts, I spotted what I thought was an Italian ex voto. As I read the words under the image, I realized it was Mexican. I was startled. I did not know the tradition had traveled so far. The object ignited dormant memories—familial, religious—which, at this point in my life, I felt the need to make room for. I began to collect Mexican ex-votos, until recently the only ones I could find.

Collecting them began as a very private affair, mainly in the service of those re-awakened memories. Each new Mexican ex-voto reminded me of one I had seen in the past, and helped me retrieve a vibrant childhood memory. But then, unexpectedly, the private act of collecting became more public, and more meaningful, as it opened up a space for new and re-newed connections–with American friends and acquaintances who liked them as well and with whom I shared, or came to share, a special bond; with relatives and friends back in Italy who, thrilled by my “return” to such a distinctive aspect of our culture, lavished me with information and beautiful books about them.

Laconic, humble, simple, and yes, so beautiful, Mexican ex-votos, like Italian ex-votos, document a religious practice of (mainly) the poor, an art form for (mainly) the poor by the poor. Simple and humble though they are, they speak with poignant eloquence about faith, class and economic inequalities, and pose challenging theoretical and ethical questions about ways of interpreting and representing them, as much as possible, on their own terms. It has been said that objects of vernacular culture should be left to be part of that culture. It has been argued that collecting them, writing scholarly articles about them, displaying them in museum exhibits, appropriates and does violence to them. But what this argument does not acknowledge is the extent to which collections, scholarship and museum exhibits can ignite respectful and responsible appreciation of cultural expressions, and artifacts that would otherwise be ignored or remain marginal.

References

Durand, Jorge and Douglas S. Massey. 1995. Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Giffords, Gloria Fraser. 1974. Mexican Folk Retablos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Haught, Nancy. “Quintana Galleries’ ex-voto exhibit presents ‘Devotional Art of the Americas’”. www. Oregonline.com

Oktavec, Eileen. 1995. Answered Prayers; Miraclces and Milagros Along The Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Salvatori, Mariolina Rizzi. “Porque no puedo decir mi cuento: Mexican Ex-votos’ Iconographic Literacy.” In Popular Literacy: Studies in Cultural Practices and Poetics. Ed. John Trimbur. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Steele, Thomas J., S. J. 1944. Santos and Saints: The Religious Folk Art of Hispanic New Mexico. Santa Fe: Ancient City.