Understanding Ex Votos

by Mariolina Rizzi Salvatori

The Latin term ex voto (short for ex voto suscepto, “from the vow made”) designates a Catholic votive offering placed in a church or shrine in thanksgiving for a miracle received. The custom of offering gifts to deities or spirits to propitiate or thank them for their protection goes back to ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Etruscan and Roman temples, gifts, called donaria, were hung on the walls next to statues of divinities, placed next to a sacred tree, and hung or buried around sacrificial altars (Pizzigoni 5). Eventually incorporated into Christian religion, the custom became a touching expression of faith in “the invisible thread that links humanity to the supernatural” (Tripputi 38).

“The premise of the Catholic ex voto is the vow,” the solemn promise supplicants make, in a moment of great hardship, to give public thanks to a particular Saint if he/she intervenes to avert disaster; the ex voto, in turn, is “the concrete testimonial of that vow’s fulfillment,” an object that stands as the material representation of the miracle itself (Pizzigoni 4). But ex votos are also offered in thanksgiving for unexpected miracles, in which case they function as public affirmations of God’s constant powerful presence in the lives of the faithful—poor or otherwise–and as records of their felt obligation to acknowledge it, to communicate it to others, to celebrate it.

The two most common types of ex votos are object ex votos and painted ex votos. The typology and materials of object ex votos vary considerably according to class and economics: they can be jewels or a wedding gown, a baptismal smock, a soldier’s uniform, a child’s Franciscan habit, a braid of hair. They can be prostheses or crutches or photographs of individuals. They can be representations of parts of the body, of internal organs, and of animals, or miniature reproductions of houses, tractors, ships, airplanes; they are made of metal–from gold to tin– or wood, wax, clay. . . Whatever their shapes, whatever they are made of, they are testimonials of faith, stories of quotidian miracles that speak to the (viewer) faithful even when the details of the miracle can only be guessed. What about the bride? And the baby? Does the ship signify shipwreck or voyage to America? In Italian the generic term for this kind of votive offerings is ex voto oggettuale (object ex voto), or miracolo (miracle). The most common is the ex voto anatomico (anatomical ex voto), an offering compellingly defined as “a biographical act that involves the body and the self” (Francis).

The two most common types of ex votos are object ex votos and painted ex votos. The typology and materials of object ex votos vary considerably according to class and economics: they can be jewels or a wedding gown, a baptismal smock, a soldier’s uniform, a child’s Franciscan habit, a braid of hair. They can be prostheses or crutches or photographs of individuals. They can be representations of parts of the body, of internal organs, and of animals, or miniature reproductions of houses, tractors, ships, airplanes; they are made of metal–from gold to tin– or wood, wax, clay. . . Whatever their shapes, whatever they are made of, they are testimonials of faith, stories of quotidian miracles that speak to the (viewer) faithful even when the details of the miracle can only be guessed. What about the bride? And the baby? Does the ship signify shipwreck or voyage to America? In Italian the generic term for this kind of votive offerings is ex voto oggettuale (object ex voto), or miracolo (miracle). The most common is the ex voto anatomico (anatomical ex voto), an offering compellingly defined as “a biographical act that involves the body and the self” (Francis).

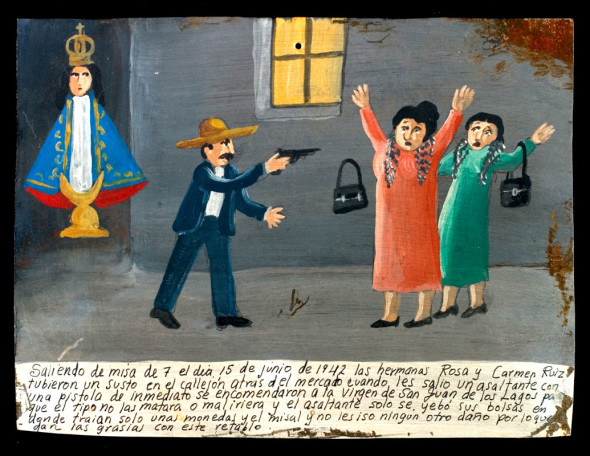

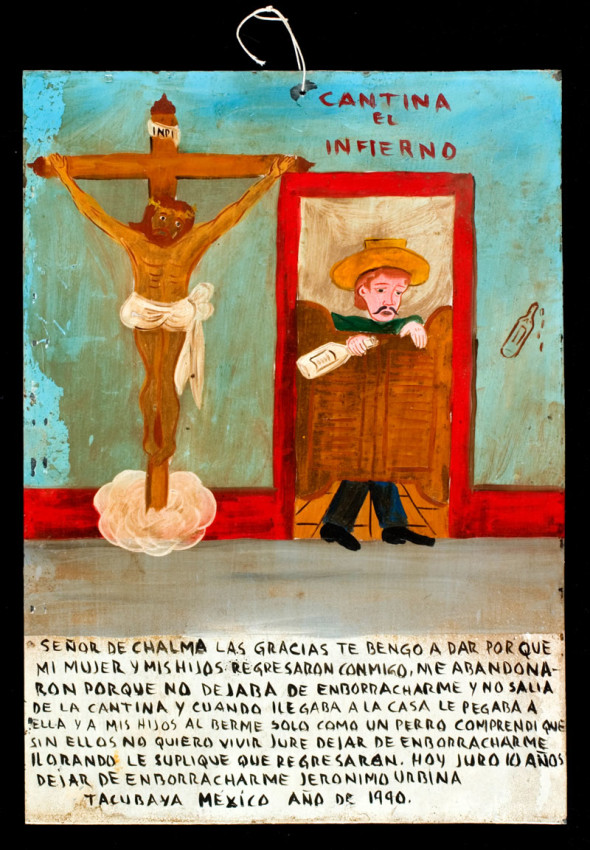

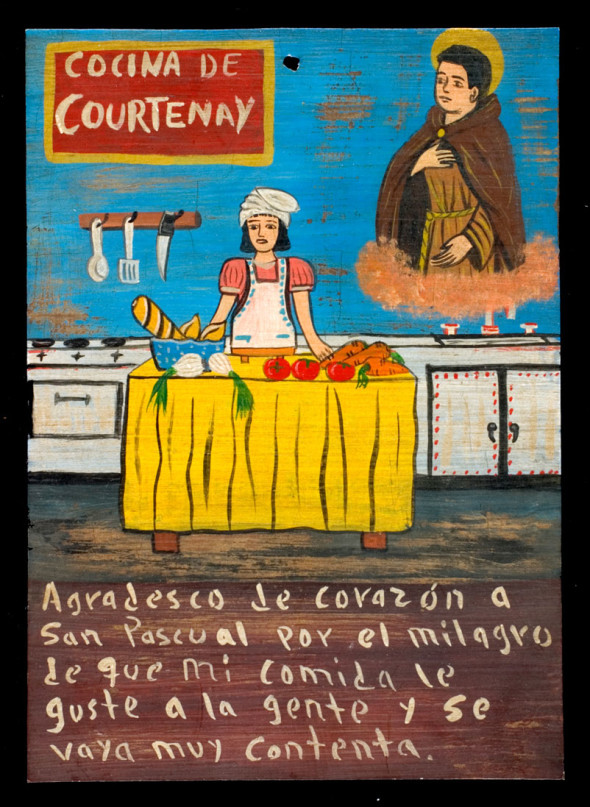

Less known outside parts of Europe, and of Mexico, is the painted ex voto (Italian ex voto, or tavoletta votiva; Mexican retablo). This tradition originated in Italy in the 15th century when wealthy patrons commissioned artists to compose a visual representation of miracles they had been granted or hoped for. According to a patron’s wealth, the painting would then be hung in a church, private chapel, or home. When the tradition spread to the less wealthy, it fell out of fashion with the upper classes. In the early part of the colonial period it spread to Europe, eventually to Latin America, reaching its height in Mexico during the middle of the nineteenth century. Some of the most significant transformations painted ex votos underwent, transformations which eventually became their distinguishing features, were the diminuition in size (from full size paintings to little paintings), the use of inexpensive materials (wood, occasionally metal laminas and glass in Italy; wood and zinc in Mexico), and the detailed visual and verbal narrative of the miracle it represented. (So central is the representation of the miracle to painted ex votos that those which only portray the supplicant are called in Italian mancanze, “something missing” (Pizzigoni 8), or segreti, “secret” (Tripputi 50)). Interestingly the “commissioning” of the painting, which originally marked status and wealth, remained as an integral part of painted ex votos well into the 20th century, although the commissioning was for much less money and often to unlettered anonymous artists. (See Salvatori, “Ex Votos’ Icongraphic Literacy”).

Less known outside parts of Europe, and of Mexico, is the painted ex voto (Italian ex voto, or tavoletta votiva; Mexican retablo). This tradition originated in Italy in the 15th century when wealthy patrons commissioned artists to compose a visual representation of miracles they had been granted or hoped for. According to a patron’s wealth, the painting would then be hung in a church, private chapel, or home. When the tradition spread to the less wealthy, it fell out of fashion with the upper classes. In the early part of the colonial period it spread to Europe, eventually to Latin America, reaching its height in Mexico during the middle of the nineteenth century. Some of the most significant transformations painted ex votos underwent, transformations which eventually became their distinguishing features, were the diminuition in size (from full size paintings to little paintings), the use of inexpensive materials (wood, occasionally metal laminas and glass in Italy; wood and zinc in Mexico), and the detailed visual and verbal narrative of the miracle it represented. (So central is the representation of the miracle to painted ex votos that those which only portray the supplicant are called in Italian mancanze, “something missing” (Pizzigoni 8), or segreti, “secret” (Tripputi 50)). Interestingly the “commissioning” of the painting, which originally marked status and wealth, remained as an integral part of painted ex votos well into the 20th century, although the commissioning was for much less money and often to unlettered anonymous artists. (See Salvatori, “Ex Votos’ Icongraphic Literacy”).

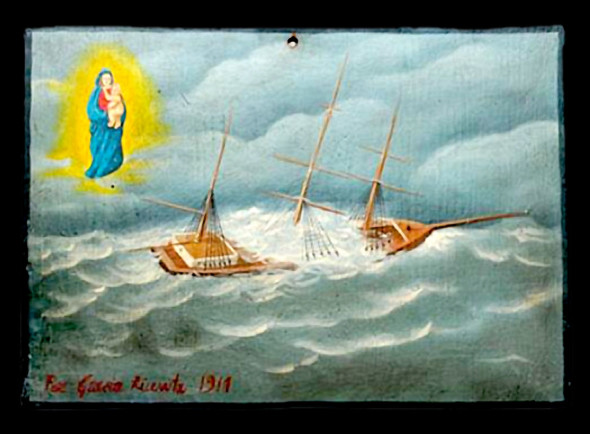

The spatial configuration of Italian painted ex votos marks two distinct and uneven parts: the smaller part, usually but not always the left upper corner, is dedicated to the heavenly figure, often floating on luminous clouds. The Saint’s gaze or outstretched hand occasionally reaches out to the supplicant, shortening “the invisible thread” between them. The rest of the space, the larger portion of the painting, is taken up by the human, and the visual representation of the miraculous event. At the bottom individualizing inscriptions: the name of the supplicant, the date of the event, only occasionally the name of the painter; votive acronyms (P.G.R, Per Grazia Ricevuta; E.V., Ex Voto; V.F.G.R., Voto Fatto Grazia Ricevuta); and/or brief written accounts of the specific miracle, often misspelled and grammatically fractured. Although painted ex votos hang on the walls of churches and shrines, they are not ecclesiastically sanctioned professions of faith. The relationship to God and His Saints they enact–direct, personal, even a bit irreverent–bypasses pastoral mediation and ecclesiastical rituals of address, which might account for the Church’s historical ambivalence toward them. As simple, deeply felt acts of faith they belong to vernacular Catholicism.

The spatial configuration of Italian painted ex votos marks two distinct and uneven parts: the smaller part, usually but not always the left upper corner, is dedicated to the heavenly figure, often floating on luminous clouds. The Saint’s gaze or outstretched hand occasionally reaches out to the supplicant, shortening “the invisible thread” between them. The rest of the space, the larger portion of the painting, is taken up by the human, and the visual representation of the miraculous event. At the bottom individualizing inscriptions: the name of the supplicant, the date of the event, only occasionally the name of the painter; votive acronyms (P.G.R, Per Grazia Ricevuta; E.V., Ex Voto; V.F.G.R., Voto Fatto Grazia Ricevuta); and/or brief written accounts of the specific miracle, often misspelled and grammatically fractured. Although painted ex votos hang on the walls of churches and shrines, they are not ecclesiastically sanctioned professions of faith. The relationship to God and His Saints they enact–direct, personal, even a bit irreverent–bypasses pastoral mediation and ecclesiastical rituals of address, which might account for the Church’s historical ambivalence toward them. As simple, deeply felt acts of faith they belong to vernacular Catholicism.

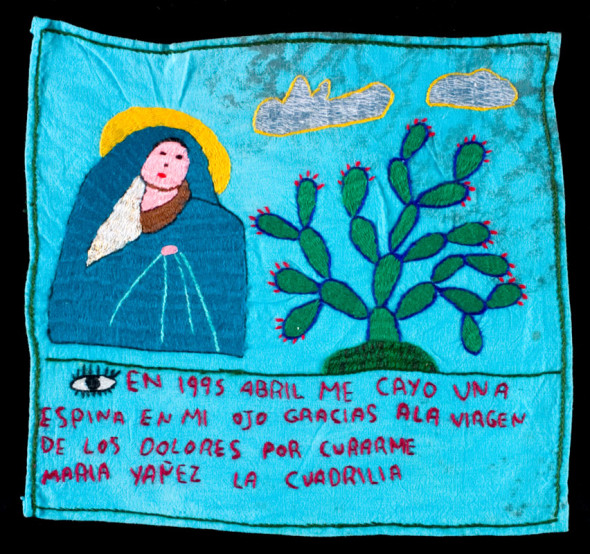

What characterizes Mexican painted ex votos (also called retablos) and distinguishes them from the Italian are the material on which they are painted, most commonly zinc, and the greater prominence they give the telling of the story, which takes up a large part of the surface. Penned mostly at the bottom are stories of miraculous recoveries from illnesses; escapes from work related accidents, fires, weather disasters; happy resolutions to stories of lost children, family feuds, military executions, broken marriages, vehicular accidents, addictions, lost jobs, emigration, crossing of the Mexican border. . . Like Italian painted ex votos, Mexican ex votos, construct a space and an audience for their poignant and sobering accounts of the daily fears, the spiritual and material needs, the dangers, the dreams and the aspirations of people that history tends to ignore. Humble and unlettered, they eloquently speak of enduring faith, class and economic inequalities, and human resilience and they pose challenging ideological and theoretical questions to scholars and collectors about ways of interpreting and representing them, as much as possible, on their own terms.

In Mexico, as in Italy, the tradition of commissioned painted ex votos is dying out . With fewer pittori di pieta’ and retablistas to commission them to, ex votos are now increasingly being made by the supplicants themselves (But consider the production of ex votos by Alfredo Vilchis Roque in INFINITAS GRACIAS and Isabella Falbo e Roberto Roda’s “ex voto laici nell’arte contemporanea“). With the advent of photography they have morphed into assemblages of prayer cards, photos, and written notes. Though perhaps less artistically appealing, they constitute a genre worthy of study (Spera 233-40). Unlike Italian culture, Mexican culture has deployed several “popular” ways of keeping alive, re-appropriating, and transforming the ex voto tradition: ex votos as souvenirs, commercially produced and sold on the streets of Mexico; ex-votos embroidered by women living in small rural communities, mainly in central Mexico, who sell them to support their families (Salvatori 38-42); decorative uses of ex votos hung in homes, offices, public places or painted on room dividers, fire place screens, refrigerator magnets (Mexicolor: The Spirit of Mexican Design).

From a religious point of view, these transformations desacralize ex votos. On the other hand the increased availability and visibility they grant them might well generate and nurture a rekindled interest in their religious and cultural function.

References

Falbo, Isabella and Roberto Roda. 2008. “Secular Ex Votos in Contemporary Art.” In Gian Paolo Borghi, Roberto Roda, and Isabella Falbo, Divine Interventions: Phenomenology of Ex Votos. Mantova: Editoriale Sometti.

Francis, Doris. 2007. “Introduction: In the Eye of the Beholder.” In Faith and Transformation: Votive Offerings and Amulets from The Alexander Girard Collection. Ed. Doris Francis. Santa Fe: Museum of International Folk Art and Museum of New Mexico Press.

Levick, Melba, Tony Cohen, Masako Takahashi. 1998. Mexicolor: The Spirit of Mexican Design. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Pizzigoni, Gianni. 2001. “Commentary.” Ex-Voto: Dipinti di Fede: Mostra di Tavolette Votive Dal XV al XIX Secolo. Milano: Tipografia Davide Mazza.

Salvatori, Mariolina Rizzi. 2001. “Porque no puedo decir mi cuento: Mexican Ex-Votos’ Iconographic Literacy.” In Popular Literacy: Studies in Cultural Practices and Poetics. Ed. John Trimbur. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Spera, Enzo. 1977. “Ex-Voto Fotografici ed Oggettuali.” In Puglia Ex Voto. Ed. Emanuela Angiuli. Bari: Congedo Editore.

Schwartz, Pierre, Victoire and Herve’ Di Rosa. 2004. Infinitas Gracias: Contemporary Votive Paintings. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books LLC.

Tripputi, Anna Maria. 2000. La Madonna di Capurso: Il Culto, La Festa, Gli Ex-Voto. Bari: Paolo Malagnino Editore.