[Italian language version]

Madonne Ritrovate . . . across the Atlantic

I have lived in USA since 1965, but I was born and educated in Southern Italy (Foggia). I grew up in my maternal grandmother’s large household where (male) agnosticism and anticlericalism lived side by side with and respectful of (female) fervent Catholicism. Among the most vivid memories of those years: an aunt of mine who used to spend morning and evening hours, every day, in her bedroom, fingering a rose bead rosary, and reading prayers from books and immaginette (prayer cards). Her lips moved silently, her head nodding slightly as she paused between prayers. Nobody interrupted her quotidian rituals. Respectful silence guarded her space. The bustle of life hushed as it passed by the door of her sanctuary.

Occasionally, cautiously, I would tiptoe into her room and would watch her, mesmerized by the material objects of her devotion–candles, crosses, immaginette, especially immaginette, which I was convinced held some magical power. Every day the same ritual–she would recite the Rosary, then she would leaf through a leather bound book of prayers, and finally, the part that most fascinated me, she would read the prayers on the verso of several immaginette meticulously fanned out on a small round table by her side: Madonna dei Sette Veli, Madonna Incoronata, Madonna Addolorata, San Giovanni Bosco, San Michele Arcangelo, Sant’Anna, Santa Lucia. . . Left to right, one card at a time. She would spend a few seconds looking at the image, then she would spin it around, read the text on the back, spin it around again, kiss the image, put the immaginetta back down in the space temporarily left empty. Day after day. Morning and evening.

Her ritual, her gestures fascinated me. But the immaginette . . . they haunted me. I longed to hold them, spin them around as she did, look at them closely. I wanted to linger on the disconcerting and frightening stories the prayers referred to: Madonna Addolorata’s (Madonna of Sorrow’s) heart pierced by seven swords; Satan screaming under St. Michael’s foot; the eyes in the little tray Saint Lucia held in her hand.

The stories woven through the prayers merged in my mind with other stories—the equally frightening, disconcerting stories my grandmother, great uncle and great aunt would often tell me on winter nights, as we sat around a large brass brazier filled with burning coals: tales by Hans Christian Andersen, the Grimm Brothers, Heinrich Hoffman, Edmondo De Amicis. . . But unlike the scary lessons of punishment those fables, common educational tools at the time, conveyed, the stories embedded in the immaginette’s prayers taught about love and endurance, gave hope and comfort, and promised forgiveness.

When in our early twenties my husband and I emigrated to the USA, this very aunt gave me as keepsake the prayer book which as a child I had so often seen her leaf through. For years I kept it stored away with other prayer books, old missals, broken rosaries, and reliquies, in my nightstand’s drawer. Then one day, while I rummaged through it, I found that book again. As I clumsily picked it up, a stream of immaginette spilled out of its pages: the immaginette as a child I had so much wanted to have. . . I took it as a sign, an exhortation. Thus began my morning ritual: reading the prayers on the verso of these immaginette, a way of praying that has taken me back to and reconnected me with a time and place so far away.

For years the memories these prayers reactivated remained stored in my heart, unshared, until recently, for the first time, and purely by chance, they spilled out, uncontrollably, as I found myself talking about immaginette with Diana George, an American colleague of mine who, educated by Catholic nuns, knew about and shared a similar connection with these humble artifacts. We spoke. We reminisced. We exchanged experiences and feelings. We began to reflect on and articulate the role of immaginette in our lives. Finally we decided to write about them from the perspective of their educational function, and their cultural and historical value. In one section of the essay we wrote (“Holy Cards/Immaginette: The Extra-Ordinary Literacy of Vernacular Religion”), I focused on a series of immaginette of Madonna dei Sette Veli, patron of Foggia, to foreground how each of them, through the particular image of the iconavetere (ancient icon) it reproduces and the relationship of that image to the prayer that accompanies it, tells a different story of and teaches a different lesson about the Madonna’s “miraculous apparition” to whom, and where, with remarkable implications for the event and its participants.

As I researched the story of Madonna dei Sette Veli, I became aware of a fascinating chapter in my region’s vernacular history, which I did not know or perhaps I had forgotten: the considerable number of icons and statues of the Virgin Mary “miraculously appearing” most often to the poor and the humble in the fields, on the shores, and in the woods of Puglia. (Puglia is not the only region, in Italy, where these icons and statues were found. According to Sicily’s vernacular history, for example, the Madonna del Tindari was smuggled out of Constantinople to be discovered in a trunk on a ship which had been forced by a storm into the port of Tindari. Joseph Sciorra, in “The Story of the Black Madonna of East Thirteenth Street,” traces the haunting story of how, thanks to the devotion of Sicilian immigrants, a replica of this Madonna “crossed the Atlantic.”)

Extending and adapting the caption “Ritrovamento del Tavolo” (the finding of the icon), which in the Annals of Foggia references and names the original finding of the icon of Madonna dei Sette Veli by several mandrians, in the year 1062, I propose to call the prayer cards that memorialize similar findings “immaginette of Madonne Ritrovate.” In other words, I propose a differential category for them so as to call attention to their specific cultural and historical, beside their filiconic, value.

The immaginette I refer to are miniaturized artistic representations of “prodigious apparitions” whose stories, passed on orally for centuries, are still kept alive in the collective memory of Pugliesi thanks to yearly elaborate and haunting reenactments of the original events, popular laudae (mostly in dialect), and, I suggest, especially thanks to the immaginette put and kept in circulation by the churches and sanctuaries erected in memory of the extraordinary event.

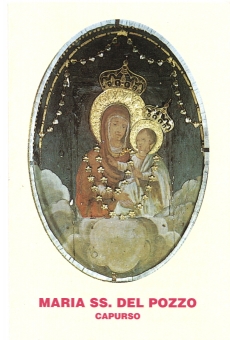

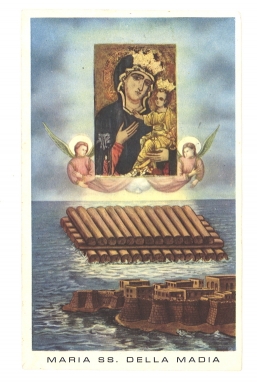

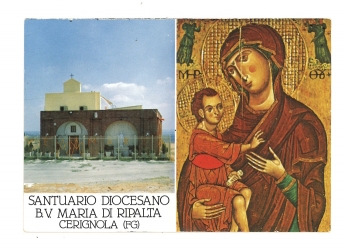

The title of each Madonna Ritrovata, prominent on the recto and verso of each immaginetta, is a reminder of the specific place where the icon was found: a well (“Madonna del Pozzo”), a barge (Madonna della Madia”), a brush (Madonna dello Sterpeto”), a high ridge in a field (“Madonna della Ripalta”). For those who are not familiar with them, in so far as these Byzantine-looking Madonnas, as it is true of most icons, much resemble each other, the title performs an important identifying function with significant economic implications, in so far as it advertises a specific church or sanctuary.

The stories these immaginette memorialize through word and image are reminiscent of ancient pagan rites of birth and re-birth. These humble artifacts then are particularly interesting from a cultural point of view. But what in my opinion makes them even more remarkable is that these stories are elaborations of a well-documented historical nucleus: the recovery of ancient icons of the Virgin Mary, brought over to Puglia and carefully hidden by Byzantine monks fleeing from Sicily, conquered by Muslims, or escaping the persecutions of Leo III Isauricus (717-741) in the Orient.

Immaginette of Madonne Ritrovate are extra-ordinary for several reasons. As collectible objects they are particularly attractive for period and style. As material expressions of vernacular faith, they serve as reassuring memories of times when the Virgin Mary is said to have made herself “present” to the humble and the poor, during their daily toils, without ecclesiastic mediation. As examples of vernacular literacy, they document the complex teaching and learning practices that undergird what might seem a simple devotional act. In fact, the words on them—from the appellation (the name of the Madonna on the front), to the invocation (the repetition of the Madonna ’s name throughout the prayer on the back), to the prayer—enact and simultaneously teach how to address the Madonna and have faith in her transcendent power.

They belong to legend, and to vernacular history. But in so far as the “apparitions” they record, in word and image, are linked to well-known iconoclastic persecutions, they also belong to official ecclesiastic history. This double belonging, I suggest, marks a significant and consequential difference between how the two genres of history remember and anchor the prodigious event.

Recently, in the U.S, immaginette have been drawing attention as objects of cultural interest, especially as “ephemera”; impressive websites have been created; several exhibits have been curated by librarians and religious studies experts; a few handsome books have been published that introduce them to a general audience; and publications by leading scholars of vernacular religion have begun to uncover their complexities. As an Italian who lives in US, I am excited by this trend, and would like to contribute to it by expanding the cultural and historical understanding of these devotional objects. For this reason, I am currently at work on a small volume to gather and fix the stories and the legends surrounding the “ritrovamenti” of the many Madonne in Puglia.

Collecting, reading and writing about immaginette I have come to realize, with increasing clarity, how important they have been in my life as an immigrant. Since they spilled out of the prayer book my aunt gifted me, my “ritrovamento” of immaginette has connected me back to the places, the time, and the culture of my childhood and youth. It is this type of memory, this lasting, complex and emotional hold they exert on the devout, that I would now like to explore. I would like then to find out which immaginette of Madonne Ritrovate made it across the Atlantic, to the United States, within the pages of a prayer book, in the pockets of an immigrant, a long distance from where the Madonna first chose to appear. Which function did they have and have retained for immigrants? Which stories have they preserved? How, by whom have these stories been told? Which cults and rituals have they established? Which sites of veneration have they contributed to erect?

It’s a difficult kind of research, I realize, maybe impossible to do. But I find its difficulty instructive and worth reflecting on: it forces me to acknowledge the loss of a rich cultural and existential patrimony immigrants often have to leave behind, a patrimony which, even if it remains a part of their identity, they cannot always easily share, and disseminate, both because it is intimately tied to specific traditions and habits of their culture, and because many of them have not been granted the cultural authority to reclaim and proclaim its meaningfulness; which urges me to try to retrace, to preserve and articulate, through them or for them, whatever fragments of that history they clang on.

References

Dipasqua, Sandra and Barbara Calamari. Holy Cards. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 2004. Print.

George, Diana and Mariolina Rizzi Salvatori. “Holy Cards / Immaginette: The Extraordinary Literacy of Vernacular Religion.” CCC 60(2) / December 2008. Print.

Hammerman, Nora. “Holy Cards Captivate at JPII Center Show.” Catholic Herald, 2 July 2005. Print.

Holy Cards: Picturing Prayers. Pope John Paul II Cultural Center, 2005. Print.

McBrien, Richard P. Catholicism: New Study Edition. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1994. Print.

—. The HarperCollins Encyclopedia of Catholicism. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1995. Print.

McGrath, Tom. “Be a Card Carrying Catholic.” U.S. Catholic Vol. 62 Issue 6 (June 1997): 50. Print.

Morgan, David. Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998. Print.

Orsi, Robert. Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars Who Study Them. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005. Print.

—. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880-1950. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985. Print.

Petruzzelli, James F. “Catholic Holy Cards: Visual, Verbal, and Tactile Codes for the (In)visible.” Eds. Cathy Lynn Preston and Michael J. Preston. The Other Print Tradition Essays on Chapbooks, Broadsides, and Related Ephemera. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1995: 266-282. Print.

Sciorra, Joseph. “The Black Madonna of East Thirteenth Street.“ VOICES: The Journal of New York Folklore, Vol. 30 (Spring-Summer 2004). Print

Stevens, Barbara. “The True Story Behind Madonnina.” St. Anthony Catholic Messenger Online. January 2000. Web. 9 Dec. 2006. (www.americancatholic.org/Messenger/Jan2000/feature1.asp).

Websites

Collezione dei santini dei Santuari Mariani – CollectorClub (www.collectorclub.it/pages/collezione_santini_santuari_mariani_4888/178)

Collezione di Santini (www.digilander.libero.it/giardinodegliangeli/Santini/Santini.html)

Le Mostre di Santini di Mario Tasca – Carmelitani di Palestrina (www.cartantica.it/pages/mostretasca2.asp

Mostra Santini Ricordo di Prima Comunione di Mario Tasca (www.cartantica.it/pages/mostretasca.asp)

Museo del Paesaggio (www.museodelpaesaggio.it/home)

Museo del Santino (www.museodelsantino.it/)

Piero Stradella (www.pierostradella.it/)

Santini di Mario Tasca al mercatino di Natale a Follina (www.venetouno.it/notizia/42904/i-santini-di-mario-tasca-al-mercatino-di-natale-a-follina)